In Memoriam: Michael Rose––the Gifted Investigator Who Revealed the Partial Meltdown at Santa Susana

On September 7, 2020, Michael Rose, a dear friend and key Bridge the Gap figure for 45 years, died of complications from a bone marrow transplant for leukemia. He uncovered some of the most important nuclear hazards in the country, which contributed to their elimination. Michael was the best researcher and investigative journalist we have ever met, and a gentle and caring soul, and he will be missed more than words can express.

After the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, Michael came across a letter from a physicist we had just received in the CBG office that included an oblique reference to a nuclear “incident” that had occurred at the Atomics International facility, now known as the Santa

Susana Field Laboratory. He began digging in technical archives and, with the aid of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, was able to bring to the news media evidence that a partial meltdown had occurred in the LA area and, until his disclosures, had been kept secret for twenty years. The revelations eventually resulted in the closure of the nuclear testing site (there had been nine other reactors at the site over time, at least three others of which also suffered accidents). The struggle to clean up the site continues to this day.

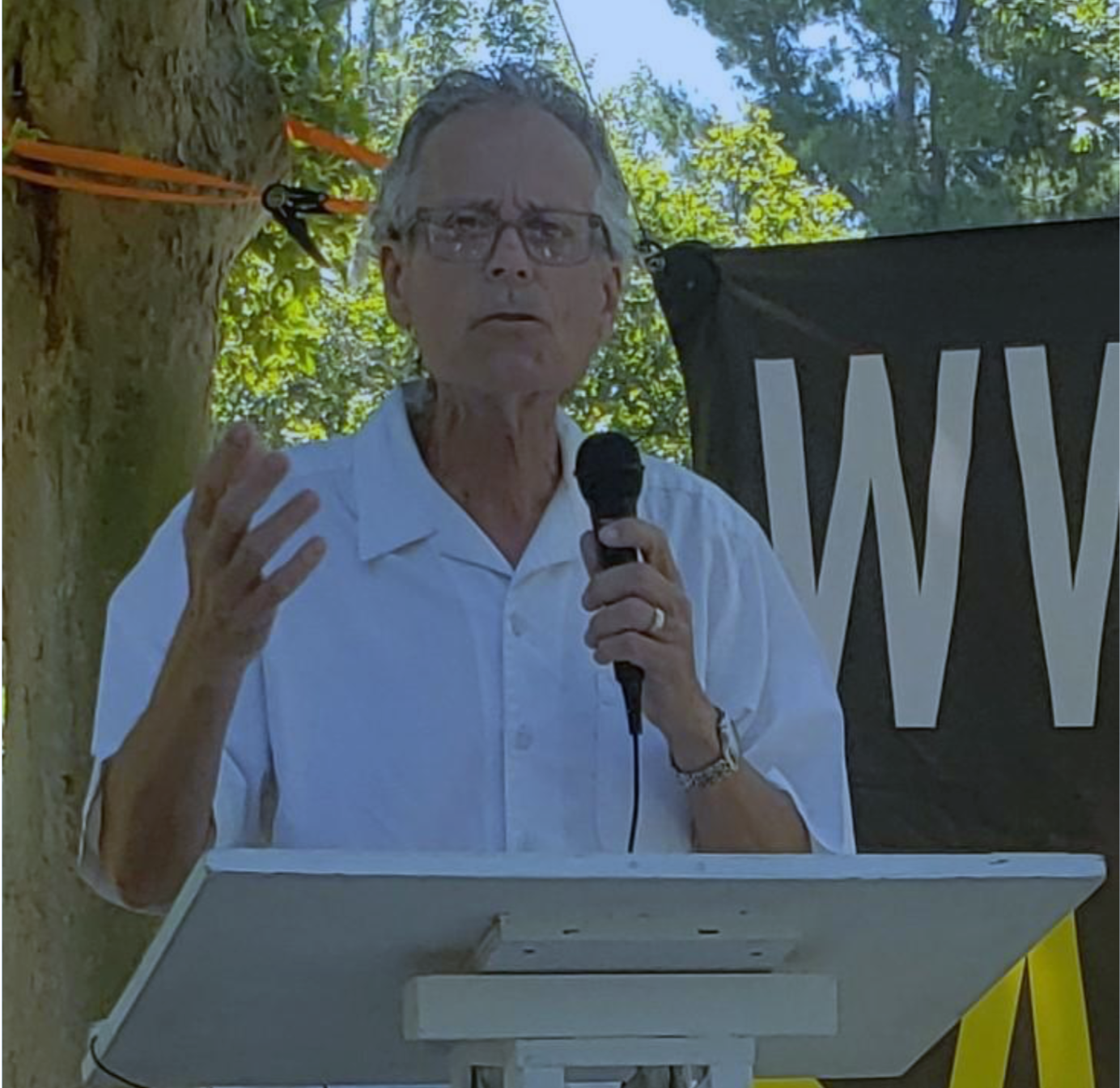

On the 60th anniversary of the partial meltdown, Michael spoke at a commemoration of the nuclear accident that the public would never have known about, had Michael not disclosed it more than forty years ago. His speech was very moving as it detailed how he brought this story to light. The community’s gratitude for what he had done was palpable.

This was by no means all he uncovered. Using FOIA requests and his extraordinary research skills, Michael soon identified the locations of fifty dumpsites for radioactive waste off the East and West Coasts and in the Gulf of Mexico. He revealed their precise longitude and latitude and the amount of radioactive waste dumped at each. The federal government had lost track of them—the EPA wrote us asking for help in locating their missing radioactive waste dumps! Michael’s work on the ocean dumping issue formed the basis for our Congressional testimony. Decades later, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal spent several days at Bridge the Gap poring over Michael’s ocean dumping documents, resulting in a major article and an interactive map showing the dumpsites Michael had uncovered. Michael’s research contributed significantly to the London Dumping Convention banning the practice of dumping radioactive waste in the oceans internationally.

Michael also helped uncover the troubled history of space nuclear power, including two radioactive sources launched from Vandenberg that failed to reach orbit. One burned up in the atmosphere and spread its plutonium worldwide; the other fell back in the LA area, spurring a frantic search to try to locate it. These revelations contributed to a decade’s worth of work by Bridge the Gap to try to stop the use of nuclear power in orbit, particularly for Reagan’s “Star Wars” orbiting battle station scheme.

Michael was also key to Bridge the Gap uncovering safety and security problems at the UCLA reactor. The reactor operators had miscalibrated the radiation monitor in the reactor exhaust stack and were thus emitting ~250 times more radioactive Argon-41 gas than they had thought and thus ~250 times more than the legal limit. It was then being sucked into the air inlet for the nearby classroom building (where I taught). Michael helped put on a packed news conference where the findings of the investigation were revealed. When a TV reporter asked what we were going to do about it, Michael whispered in my ear to say that we would intervene in the relicensing proceedings for the reactor, which I then said, beginning a five-year struggle that resulted finally in the closure of the reactor. We also discovered that the reactor operators had been storing five nuclear bombs’ worth of weapons-grade uranium in a filing cabinet with security no better than the campus bookstore, which eventually resulted in successfully pushing the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to ban bomb-grade uranium in reactors.

This is a key ingredient of Michael’s story—he was a superb researcher and investigator, but he wanted to be behind the camera helping tell the story, not be the story himself. In part this was due to his gentle humility, and in part because his passion was to be a documentary filmmaker or producer of TV news investigations and he felt that if he were known as an activist, that would make that prospect more difficult. He wanted to uncover injustices and environmental problems in a way that would give ammunition for others to fight to remedy them. He had me testify before the Congressional committee holding hearings on ocean dumping of radioactive waste, presenting Michael’s findings of the 50 ocean dumpsites. He came with us to San Francisco to prepare to testify before a federal panel on radiation, but wanted me to do the testimony. I remember meeting in a small coffee shop near Westwood, shortly after Michael’s discovery of the meltdown had been aired on NBC-LA for a week, to help shape what I should say about it in testimony before the Ventura County Board of Supervisors. Michael uncovered great revelations, and in some fashion, Bridge the Gap has spent the last forty years working to address the problems he disclosed.

His great passion was to uncover and reveal. So, while working with Bridge the Gap, Michael worked diligently to break into the TV news and documentary business.

At one point, a local television station aired a two-hour propaganda piece in favor of more nuclear weapons. Michael suggested Bridge the Gap use the Fairness Doctrine—which has regrettably now been revoked—to demand equal time. Which we got! Michael produced an honorable counter show, hosted by the actor Robert Walden of the Lou Grant Show, about why the nuclear arms race needed to be reversed, which they aired.

I remember Michael and me racing to the ABC bureau in LA to provide them with footage Michael had acquired of leaking radioactive waste barrels in the ocean so they could “bird it” (transmit via satellite) to Bettina Gregory of ABC National News in Washington, and watching a few hours later when it was used on the national news for a story about radioactive waste dumping in the ocean. Michael also came up with a great story that Bridge the Gap tried unsuccessfully to get covered about the reactor from the Seawolf, an early nuclear submarine, that was dumped off the Maryland-Delaware coast. It was the largest piece of intentionally dumped radioactive waste and could no longer be located. Jimmy Carter had been an officer for the Seawolf when in the Navy.

In 1982-3, Michael co-created and produced a magnificent public affairs show on national security issues on KPFK with world-class interview subjects hosted by Ian Masters; now known as “Background Briefing,” the show continues to this day. He worked with the Community Information Project, an investigative news show out of KCET, the public television station in LA, and helped create segments for 60 Minutes and 20/20. He produced and wrote for KCET an hour-long special on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. He developed a mini-documentary for KABC disclosing the history of accidents involving U.S. space nuclear power.

I remember us going together to a small office near KCET to meet with people from what became the Center for Investigative Reporting, trying to pitch to them Michael doing a story about another of his amazing discoveries—that there had been two nuclear weapons tests off the California coast that had so scared the fishing industry that they were worried people would stop eating fish caught there due to the radioactivity. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the fishing industry had collaborated on a ridiculous cover story that the area where the bombs went off was a “fish desert,” and then put up Geiger counters over the conveyor belts for the fish to be able to claim there was no radioactivity in them, knowing full well the monitors couldn’t pick up contamination at the levels of concern. Michael, as usual, had found a raft of dynamite documents and film footage; they were compelling TV, and on an important issue. The guys we met with were impressed with Michael and the story; that wasn’t the problem. The problem was that it was too good of a story, too important; in a word, it was too dangerous for a business that had become increasingly focused on coverage of car crashes and movie stars, and increasingly dependent upon and scared of offending corporate advertisers and sponsors.

My memory is that this meeting was a turning point for Michael. Shortly thereafter he moved to Detroit to work for GM making industrial films, in order, he said, to learn how to use top professional filmmaking equipment in the hopes of then using those skills to make documentaries himself. Others can give more detail of what happened thereafter. He met the love of his life, Carol King, and commenced a marvelous and joyful partnership with her. After 13 years, they returned to LA, set up Michael Rose Productions, and together tried diligently to make the kind of documentaries he had the investigative and filmmaking skills to produce. But he continued to face that fundamental wall making it difficult to air serious stories that might shake up the powers-that-be. He could get The History Channel to run documentaries about different automobiles, but he came up against brick wall after brick wall trying to produce and air documentaries about the pressing matters that afflict our world. Michael’s knowledge of history meant his docs about automobiles weren’t just about cars, they told the true story behind them. He described what the engineers, designers, dreamers, and automotive pioneers were trying to achieve, and explored their successes and failures. He went behind the scenes to tell the tales of some of the most legendary and charismatic people the world has ever known — Henry Ford, Enzo Ferrari, John DeLorean, Lee Iacocca, Dr. Ferdinand Porsche and some of the scalawags and scoundrels who shaped the automotive industry, which made his documentaries compelling.

He tried over and over again to get interest in a documentary on the Santa Susana Field Lab (SSFL), the site of the partial meltdown which he had exposed forty years ago. Over and over again he was rebuffed. The site is largely owned by the Boeing Company, and Boeing is an important sponsor of PBS and other outlets.

Michael at one point tried to do a documentary about Walter Reuther, the late United Auto Workers President, and the labor movement, but everywhere he went (e.g. the History Channel) he was turned down. Corporations get all the air time they want; labor is ignored. As he wrote me a few weeks ago, “After History and all the others took a pass, I raised some money and pulled together a team to make a short doc for next to nothing. I was able to get it on the local PBS station in Detroit. They were so worried about offending any of the car makers that they aired it at 3 AM. Hoping no one would see it. Entered it in the local Emmys and we won but only a handful of people saw it. As my dad said, news is what they don’t want you to read, or in this case, to see and hear. That fits the SSFL.”

During all these years Michael continued to help Bridge the Gap. He transferred to video and then to DVD the AEC film footage of the meltdown he had helped uncover so many years ago; he made it available as “B roll” to reporters when we did news events like the 50th anniversary of the accident or were part of the release of public health studies showing excess cancers among the site workers. He converted to electronic form large numbers of old videos of news stories about us. Last year he attended the NASA hearings on its proposal to break its cleanup agreements for SSFL and protested when I was surrounded by eight policemen while waiting quietly in line to testify and was escorted out, preventing my testimony. He was always there for thoughtful advice, about our work or about personal matters with which I was struggling. A kind, kind, thoughtful soul.

For the last several years Michael had been trying to gain support for a documentary about an amazing and important story—the successful David-and-Goliath battle between one of the most powerful, and racist, men of his time, Henry Ford, and a courageous yet unknown figure named Aaron Sapiro. As Michael described it, “Many don’t realize that Ford was … the most influential anti-Semite in American history.” Despite Ford’s immense power, Sapiro sued and beat Ford, resulting in a public apology and the closure of Ford’s viciously anti-Semitic newspaper.

Michael’s efforts to produce this important film were continuously frustrated. The Ford Motor Company is, of course, a major advertiser for commercial networks, and the Ford Foundation a major sponsor for public television. An unflattering documentary about Henry Ford would take courage, and courage is in short supply in the media.

So Michael decided in the end to turn his research into a book. He had finished a major part of the book when he had to go into the hospital for the bone marrow transplant. He had tried to postpone the transplant a few weeks longer in order to complete the book, but his blood levels had dropped, and the schedule for the procedure had to be moved up.

He went into the City of Hope on August 21 and had the transplant on August 28. He knew it was a risky procedure, but had no choice, and faced it all with courage. We emailed back and forth while he was in the hospital. My last email to him was on the afternoon of September 5, to let him know my house—and all the Bridge the Gap files, including the extraordinary documents his research had uncovered over the years—had been spared the raging fires by about a hundred feet.

A few hours later Michael suffered a brain hemorrhage and he was placed in a medically- induced coma and onto a ventilator. Surgery the next day to relieve the pressure brought a cascade of complications, and in the early morning hours of September 7, we lost him.

But so much of him lives on. His work made possible both the closure of the dangerous reactor testing site at Santa Susana and the continued work of so many to get it finally cleaned up. Dumping of radioactive waste in the oceans is now prohibited worldwide. The idea of using nuclear power sources in orbit has largely been abandoned.

Much of Bridge the Gap’s work continues to build on what Michael uncovered and to carry out efforts to remedy those threats to the environment.

He deserved twenty more years, at least. And he deserved a society where the kind of documentaries and investigative news stories exposing injustices and environmental threats for which his extraordinary research skills were so well suited could see the light of day. Long ago A. J. Liebling famously said that in the United States we have freedom of the press—for anyone rich enough to own a press. In our era the situation is even worse, as one needs to be rich enough to own a cable network. The powerful interests Michael wanted to expose had powerful influence over the media necessary to approve/fund/air the exposé.

Like Aaron Sapiro v. Henry Ford, our society knows who Ford was and doesn’t know who Sapiro was. But Sapiro struck a blow for justice, and when it comes time for names to be engraved in the Book of Life, Sapiro’s will be there and Ford’s will not, and Michael Rose’s will be there, and Boeing’s will not.

Michael was a gentle, thoughtful, soft-spoken, caring person of great talent, and a beloved friend. Much of Bridge the Gap’s work for decades has been carrying out battles on matters he uncovered, and that work—his work—will continue.

Michael wrote, “Storytelling has been my passion since college where I discovered the power of media to make social change. At UCLA I decided to find a way to channel this interest into producing documentaries. My Project One in the film school sparked an ongoing investigation into the aftermath of a secret nuclear reactor meltdown I discovered that had taken place in the San Fernando Valley.” After describing how that work has continued to reverberate in the years since, Michael concluded, “What I’ve learned is the power of a story, like radiation, can have a long half-life.” Michael’s work uncovering stories that move forward the struggle for justice will have a long half-life. But we will miss thee.

Dan Hirsch

Committee to Bridge the Gap